Where do you begin with the mountain of documentation required to comply with NIST SP 800-171? First, let’s clarify the difference between a policy and a procedure. A policy is essentially a guideline that outlines what an organization must do. It doesn’t need to be overly complex. In fact, I prefer simple policies because if I handed them over to my wife’s middle school students, they would still understand them and know what to follow. For example, a policy can be stated in different ways but still convey the same meaning:

- The IT Department will configure the information system to automatically lock accounts after the session idle time or unsuccessful logon attempts have been reached as outlined in the organizationally defined parameters document.

- The IT Department will configure the information system to enforce a system lockout for 30 minutes once the total unsuccessful logon attempts have reached 5 attempts within a 15-minute interval. In addition, the information system shall be configured to lock an account once a session’s idle time has reached the 15-minute mark, at which time reauthentication should be required.

The first option lacks all the organizationally defined parameters (ODP) for a few reasons. First, end users don’t need to know the specific configurations of the information system. Second, and more critically, while it may be called an ODP, who is actually defining it? If you started to point to the contract-issuing agency, you’d be on the right track.

What happens when an agency defines a parameter that you must change in the information system? You’ll need to update the relevant policy, procedure, and possibly other documentation. This involves making the change, reviewing it, and then approving and publishing the updated documentation. Things would be much easier by directing all ODP items to a single document which undergoes the change review/approval process.

To determine who ultimately defines an ODP, it would escalate to the Original Classification Authority (OCA), which decides how information is classified. The flow-down information should include a Security Classification Guidance (SCG). The SCG is a crucial document that outlines why something is considered Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI) and specifies any distribution restrictions in place.

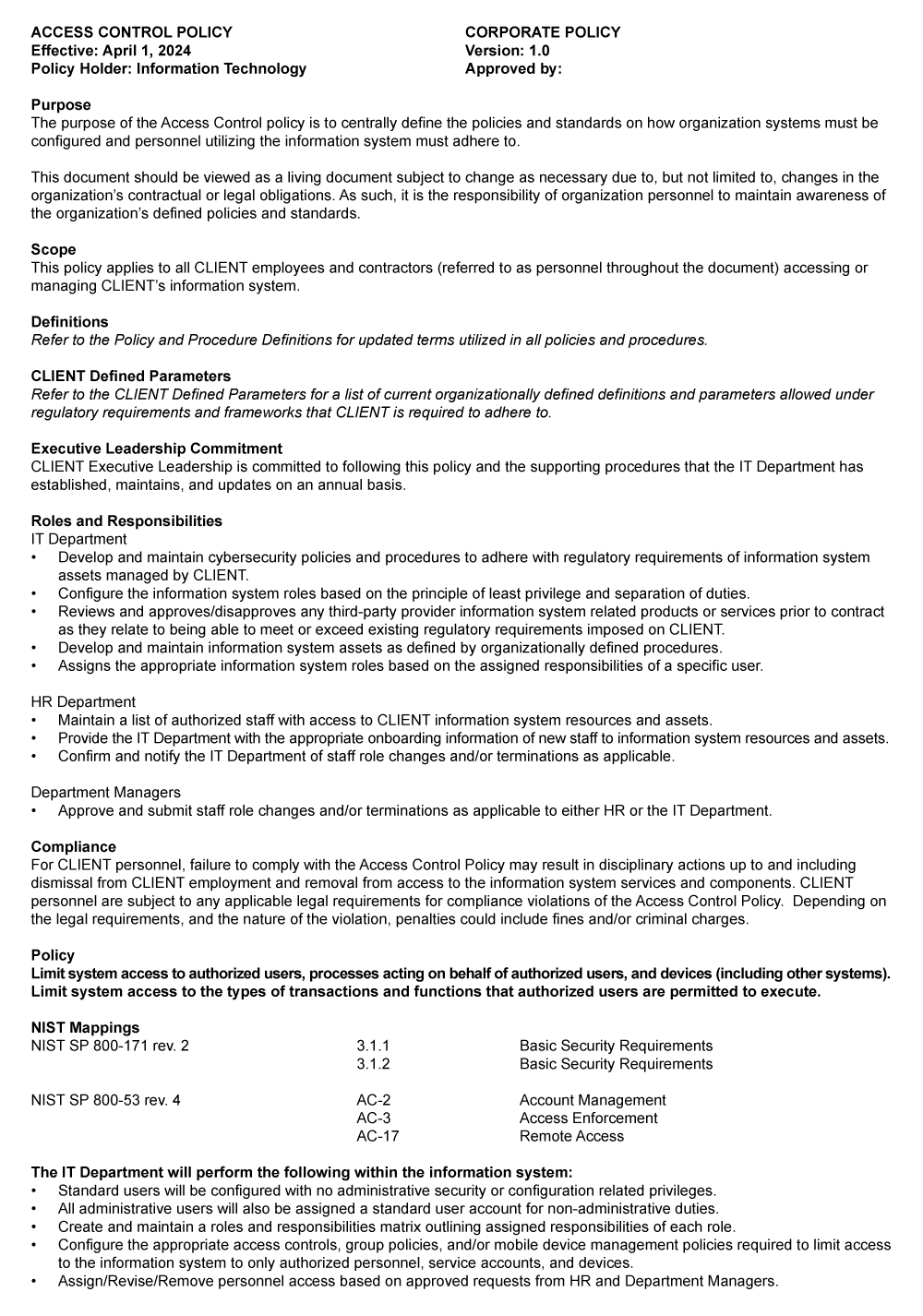

For those that prefer a little more of a visual here’s an example out of our Access Control Policy for reference:

Click Image to Expand

As demonstrated in the example, a policy typically includes a purpose, scope, definitions (optional), parameters, executive commitment, responsibilities, compliance, and is followed by each policy. Is this the only way to create a policy? Not necessarily, but this is the approach we used for our clients. The key rule of thumb is that the policy should be understandable by everyone, not just those who wrote it or those with a thesaurus that includes Latin and legal jargon.

Moving on to procedures, they simply outline the steps required to implement a policy. For example, consider the first assessment objective under 3.1.1 in access controls, which asks if authorized users are identified. To explore this further, how are authorized users identified? Many IT professionals might respond with “Active Directory,” which is partially correct. However, consider the process for getting someone into Active Directory—how does that happen? This often prompts deeper thinking during consulting discussions. The typical response might be, “Well, HR manages our employee records,” which is also correct but incomplete. To determine the proper procedure, you need to examine the control and assessment objective to ask the right question. In this case, the question would be:

How am I limiting access to the information system to only identified authorized users?

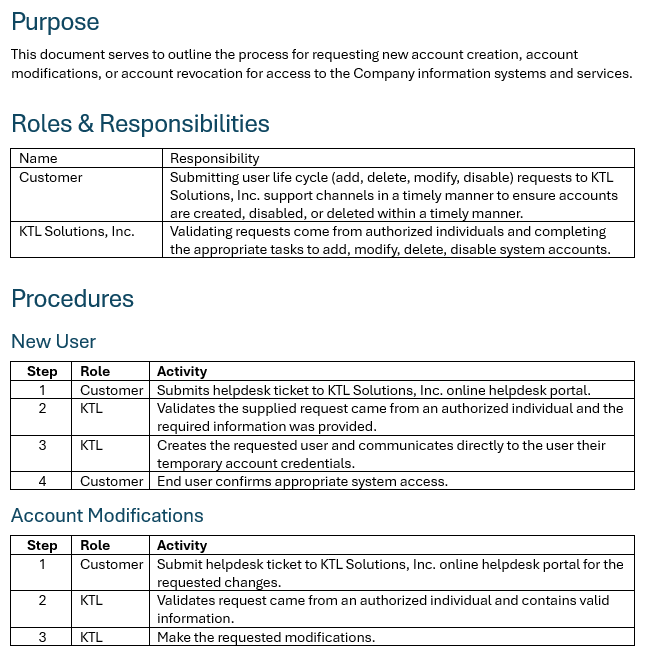

Typically, the answer then shifts to an undocumented process involving submitting an IT ticket using a pre-populated template for account requests. Many organizations have such processes but haven’t documented them until now. Although it might seem trivial, it’s often that straightforward. However, there will be times when existing processes need to be updated to meet compliance requirements, which will require time and training. For processes that are already in place but just need to be documented, keep it simple. We usually use a step, role, and activity format, but procedures can take any form that suits your organization. Here’s an example of our procedure for KTL 360 services:

Click Image to Expand

Keep in mind that while the procedure example provided is basic, there’s an underlying IT ticket format that captures all the necessary information required as evidence during an assessment. This ensures that the data collected as part of the IT ticket meets the necessary compliance standards.

Writing policies and procedures doesn’t have to be overly complicated, but it does require time and thoughtful consideration. These documents don’t need to be step-by-step instructions; rather, they should provide enough guidance so that a trained individual can effectively complete a task.

If you’d like a full copy of our Access Control Policy, ODP document, or the KTL 360 Account Lifecycle Procedure, please schedule a meeting with one of our Account Executives to learn more about KTL’s Microsoft services and solutions at sales@ktlsolutions.com.

If you’re conducting a self-assessment against the NIST SP 800-171 guidelines in preparation for the final rulemaking of CMMC, we invite you to download a copy of our self-assessment tool here.